Image Credits: TechCrunch

Aphone surveillance app called Spyhide is stealthily collecting private phone data from tens of thousands of Android devices around the world, new data shows.

Spyhide is a widely-used stalkerware (or spouseware) app that is planted on a victim’s phone, often by someone with knowledge of their passcode. The app is designed to stay hidden on a victim’s phone’s home screen, making it difficult to detect and remove. Once planted, Spyhide silently and continually uploads the phone’s contacts, messages, photos, call logs and recordings, and granular location in real-time.

Despite their stealth and broad access to a victim’s phone data, stalkerware apps are notoriously buggy and are known to spill, leak, or otherwise put victims’ stolen private data at further risk of exposure, underlying the risks that phone surveillance apps pose.

Now, Spyhide is the latest spyware operation added to that growing list.

Switzerland-based hacker maia arson crimew said in a blog post that the spyware maker exposed a portion of its development environment, allowing access to the source code of the web-based dashboard that abusers use to view the stolen phone data of their victims. By exploiting a vulnerability in the dashboard’s shoddy code, crimew gained access to the back-end databases, exposing the inner workings of the secretive spyware operation and its suspected administrators.

Crimew provided TechCrunch with a copy of Spyhide’s text-only database for verification and analysis.

Years of stolen phone data

Spyhide’s database contained detailed records of about 60,000 compromised Android devices, dating back to 2016 up to the date of exfiltration in mid-July. These records included call logs, text messages, and precise location history dating back years, as well as information about each file, such as when a photo or video was taken and uploaded, and when calls were recorded and for how long.

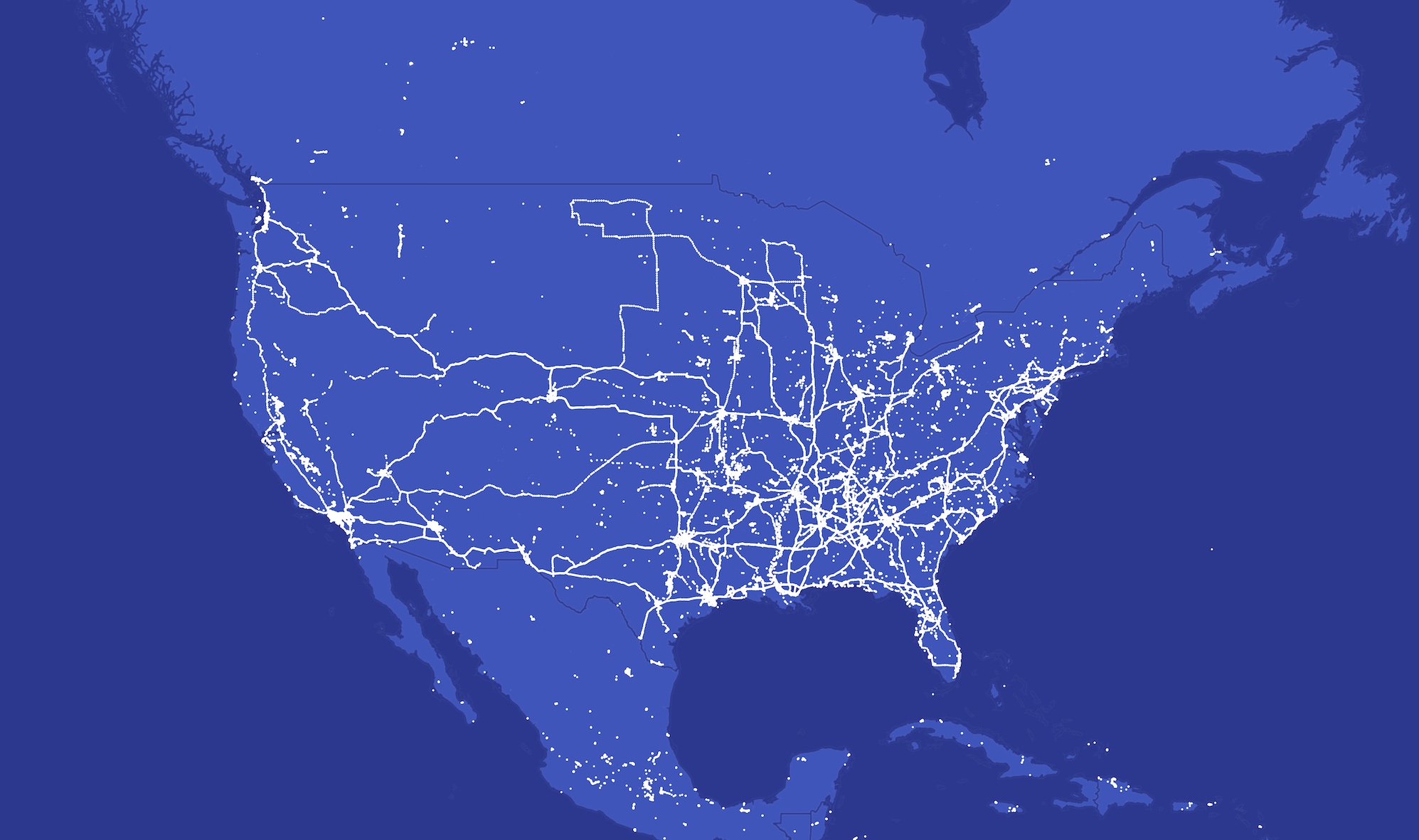

TechCrunch fed close to two million location data points into an offline geospatial and mapping software, allowing us to visualize and understand the spyware’s global reach.

Our analysis shows Spyhide’s surveillance network spans every continent, with clusters of thousands of victims in Europe and Brazil. The U.S. has more than 3,100 compromised devices, a fraction of the total number worldwide, yet these U.S. victims are still some of the most surveilled victims on the network by the quantity of location data alone. One U.S. device compromised by Spyhide had quietly uploaded more than 100,000 location data points.

Image Credits: TechCrunch

Spyhide’s database also contained records on 750,000 users who signed up to Spyhide with the intention of planting the spyware app on a victim’s device.

Although the high number of users suggests an unhealthy appetite for using surveillance apps, most users who signed up did not go on to compromise a phone or pay for the spyware, the records show.

That said, while most of the compromised Android devices were controlled by a single user, our analysis showed that more than 4,000 users were in control of more than one compromised device. A smaller number of user accounts were in control of dozens of compromised devices.

The data also included 3.29 million text messages containing highly personal information, such as two-factor codes and password reset links; more than 1.2 million call logs containing the phone numbers of the receiver and the length of the call, plus about 312,000 call recording files; more than 925,000 contact lists containing names and phone numbers; and records for 382,000 photos and images. The data also had details on close to 6,000 ambient recordings stealthily recorded from the microphone from the victim’s phone.

Made in Iran, hosted in Germany

On its website, Spyhide makes no reference to who runs the operation or where it was developed. Given the legal and reputational risks associated with selling spyware and facilitating the surveillance of others, it’s not uncommon for spyware administrators to try to keep their identities hidden.

But while Spyhide tried to conceal the administrator’s involvement, the source code contained the name of two Iranian developers who profit from the operation. One of the developers, Mostafa M., whose LinkedIn profile says he is currently located in Dubai, previously lived in the same northeastern Iranian city as the other Spyhide developer, Mohammad A., according to registration records associated with Spyhide’s domains.

The developers did not respond to several emails requesting comment.

Stalkerware apps like Spyhide, which explicitly advertise and encourage secret spousal surveillance, are banned from Google’s app store. Instead, users have to download the spyware app from Spyhide’s website.

TechCrunch installed the spyware app on a virtual device and used a network traffic analysis tool to understand what data was flowing in and out of the device. This virtual device meant we could run the app in a protective sandbox without giving it any real data, including our location. The traffic analysis showed that the app was sending our virtual device’s data to a server hosted by German web hosting giant Hetzner.

When reached for comment, Hetzner spokesperson Christian Fitz told TechCrunch that the web host does not allow the hosting of spyware.

What you can do

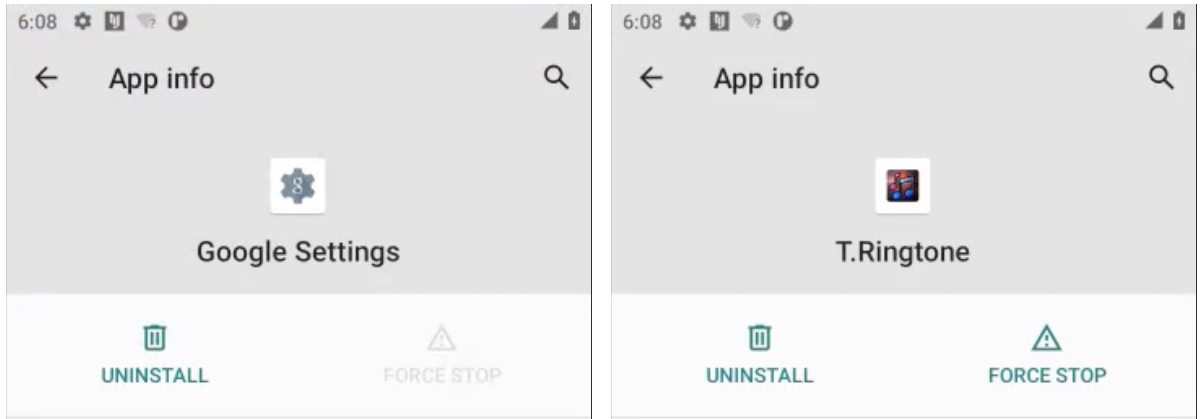

Android spyware apps are often disguised as a normal-looking Android app or process, so finding these apps can be tricky. Spyhide masquerades as a Google-themed app called “Google Settings” featuring a cog icon, or a ringtone app called “T.Ringtone” with a musical note icon. Both apps request permission to access a device’s data, and immediately begin sending private data to its servers.

You can check your installed apps through the apps menu in the Settings, even if the app is hidden on the home screen.

Image Credits: TechCrunch

We have a general guide that can help you remove Android spyware, if it’s safe to do so. Remember that switching off spyware will likely alert the person who planted it.

Switching on Google Play Protect is a helpful safeguards that protects against malicious Android apps, like spyware. You can enable it from the settings menu in Google Play.

10:29 AM

10:29 AM